Nicaraguan Journal

In this photo Coffee Works owner John Shahabian participates with Alex Mason of Royal Coffee in a cupping at the beneficio seco of Prode Cooperativa near Esteli in northern Nicaragua.

A highlight of our trip to Nicaragua was being able to cup the new crop and get a preview of the future offerings from each producer.

The photos on this page illustrate the coffee production cycle as practiced at two renowned specialty coffee growers and suppliers in Nicaragua. As you can see, the production of high-quality coffee for enjoyment by enthusiasts around the world is an exacting and time-consuming labor of love.

(Click on all photos to view enlarged).

Coffee is grown in the high mountains of Nicaragua, at 1200 meters (4,000 ft) and above, in places that receive over 3 meters (9+ feet!) of rainfall a year. The natural beauty and serenity of the Central American landscape are a constant distraction for the visitor. Scenes like this of sunlight streaming through storm clouds offered routinely spectacular vistas. More importantly, they are necessary to produce the ideal climate for nurturing the delicate, high-grown coffee flavor we seek.

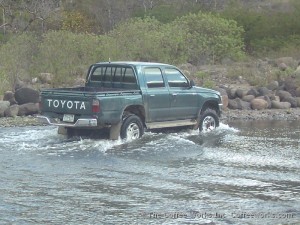

Here we cross a river on the way to our destination, a remote co-op farm situated inside the wild Miraflor National Preserve in Nuevo Segovia state.

Once you leave the Pan American highway most northern Nicaraguan coffee lands are only accessible in 4 wd vehicles on unpaved roads.

Mild coffee arabica flavor is best developed, as here on the Selva Negra plantation near Matagalpa, when the coffee trees are interplanted under a canopy of fruit and shade trees.

There are still some relics of the Somoza era littering the Nicaraguan landscape, like this rusty vintage tank which sits near where it gave up the ghost. It now serves as a roadside landmark, it’s canon pointing the way to the Selva Negra coffee plantation.

We were fortunate to witness the day’s harvest being received at a roadside collection spot on the plantation. Pickers are paid by the coffee grower for each cajuela (a dry measure that is equal to about 20 kilos or 44 pounds) of berries they harvest. Here under the watchful eye of the pickers the day’s harvest is measured by the plantation buyer. Coffee cherries spill out on the ground as they are poured into the cajuela, counted, and poured back into bags.

At this facility the freshly-picked coffee cherries are trucked immediately to the wet mill to be put through a mechanical de-ping. It is a critical step in “euro-prep” coffee production that the pulp of the fruit is promptly striped off before it has time to decay and potentially give an off taste or sourness to the seed (coffee beans).

At the much more primitive cooperatively-owned wet mill in Miraflor, the de-pulping machine is powered by a small gasoline engine. This was the only piece of motorized equipment at this remote facility. Though less well-equipped than plantation growers, the small family farmers of the co-op manage through intimate care and much physical labor to produce a coffee which is routinely superior in flavor to highly mechanized operations in neighboring regions.

Immediately following de-pulping, the coffee cherries go into a water-filled fermentation tank overnight, which loosens a stubborn sticky layer of pulp that adheres to the seed. Following this soaking the membrane can be rinsed off.

At the low-tech Miraflor wet mill, after fermentation the coating is rinsed off in clean water diverted from a local spring. Here the freshly rinsed coffee seeds are being scooped into bags to be carried on their backs up the hill to a sunny patio for their first drying.

In this initial drying, a member of the co-op carefully picks out any seeds which were crushed during milling or display any other defect. The coffee seeds are ready to be bagged for shipment to the dry mill when they have reached a nice golden color (oreada). At that stage the beans are still enclosed in an outer parchment skin which protects them from deterioration, and coffee in this state is known as pergamino. The pergamino from this grower co-op goes exclusively to the dry mill (beneficio seco) of the Prode co-op near Esteli.

In this photo the natural forms of the hills of drying coffee seem to mimic the awesome beauty of the surrounding terrain.

Overlooking the drying yard of the Prode Cooperativa. Coffees from the member farms arrive and are piled for closer inspection and more drying. They are moved in turn to the patios on the left where they are spread out flat and frequently turned and raked until they reach a final stable dryness. The fully dried pergamino is then re-bagged and labeled for interim storage.

Co-op director Merline (far left) with Organic Crop Improvement Association inspectors discussing the coffees drying at the cooperativa’s beneficio.

The reason for so many separate little piles of coffee is so organic certification auditors are able to track each individual batch back to it’s original farm. The green tag in the center of the pile holds its identification paperwork.

This modern coffee milling plant is the pride of the growers cooperativa, purchased with the support and loans from the national government and international agencies. Milling the parchment covering, polishing, and sorting the beans are final steps before bagging for shipment.

Owning their own mill and shipping plant has allowed the farmers of this co-op to gain final control over product quality, earn their own recognition and distinction, and to realize more of the value of their labors, a win for both them and consumers.

After machine milling and mechanical sorting, in the final step before bagging, the coffee still must pass muster by the beautiful women of the co-op, whose discerning vision and skillful hands cull out any final defects missed by the machines. There are approximately 2,000 beans in a single pound of coffee representing an incalculable amount of labor and care.

At the end of the line the jute bags are filled, individually sewn, and stacked ready for export. Each bag weighs 60 kilos (132 lbs). A shipping container holds 250 bags (37,500 lbs) of coffee, the standard shipping quantity. This is what one looks like with the outer container peeled off.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!